What does the term ‘As thick as thieves’ mean?

We might expect ‘as thick as thieves’ to be a variant of the other commonly used ‘thick’ simile ‘as thick as two short planks’. The fact that the former expression originated as ‘as thick as two thieves’ gives more weight to that expectation.

As you may have guessed from that lead in, the two phrases are entirely unconnected. The short planks are thick in the ‘stupid’ sense of the word, whereas thieves aren’t especially stupid but are conspiratorial and that’s the meaning of ‘ thick’ in ‘as thick as thieves’.

‘Thick’ was first used to mean ‘closely allied with’ in the 18th century, as in this example from Richard Twining’s memoir Selected Papers of the Twining Family, 1781:

Mr. Pacchicrotti was at Spa. He and I were quite ‘thick.’ We rode together frequently. He drank tea with me.

Like all ‘as X as Y’ similes, ‘as thick as thieves’ depends on Y (thieves) being thought of as archetypally X (thick). The thieves had some competition. Earlier versions were ‘as thick as’… ‘inkle weavers’, ‘peas in a shell’ and ‘three in a bed’, all of which were examples of things that were especially intimate (inkle-weavers sat at looms that were close together).

These variants have now pretty much disappeared, leaving the way clear for ‘as thick as thieves’.

via Phrase Finder.

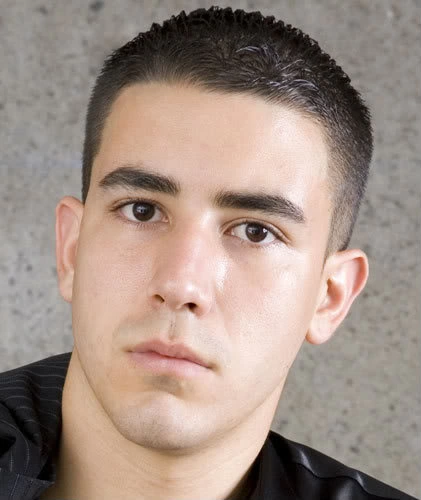

1950s Men’s Hairstyles.

All I can say as an old Aussie who was a youngster in the 1950s is that I wish our Aussie barbers were as good as these American barbers back then.

All I can say as an old Aussie who was a youngster in the 1950s is that I wish our Aussie barbers were as good as these American barbers back then.

So I put I put a picture on the front of Vincent D. “Gomer Pyle” from Stanley Kubrick’s “Full Metal Jacket” which is more like the Australian Crewie that I used to be given back then.

Crew cut hairstyle.

The crew cut style has a significant meaning for the men choosing to wear it. This haircut held symbolic meaning that meant hard work ethics.

In fact, this style was adopted by the military to replace the old style, traditional buzz cut.

The reason for this change was how well the meaning behind the crew cut was taken by those around the wearer.

Source: Most Popular 1950s Mens Hairstyles – Cool Men’s Hair

Pepsi was originally known as “Brad’s Drink”.

Caleb Bradham of New Bern, North Carolina was a pharmacist.

Like many pharmacists at the turn of the century he had a soda fountain in his drugstore, where he served his customers refreshing drinks, that he created himself.

His most popular beverage was something he called “Brad’s drink” made of carbonated water, sugar, vanilla, rare oils, pepsin and cola nuts.

“Brad’s drink”, created in the summer of 1893, was later renamed Pepsi Cola in 1898 after the pepsin and cola nuts used in the recipe.

In 1898, Caleb Bradham wisely bought the trade name “Pepsi Cola” for $100 from a competitor from Newark, New Jersey that had gone broke.

via The History of Pepsi Cola – Caleb Bradham.

A Lesson in Brushwork with Elizabeth Yeats.